In a quiet corner of Japan's hot spring region, a curious culinary experiment has been quietly unfolding for the past three years. A group of food scientists and thermal biology enthusiasts have been exploring the possibilities of human-body-temperature egg incubation, using the naturally occurring warm waters of onsens as their laboratory. This unconventional approach to egg preparation challenges traditional cooking methods and raises fascinating questions about food chemistry, microbiology, and the very nature of cooking itself.

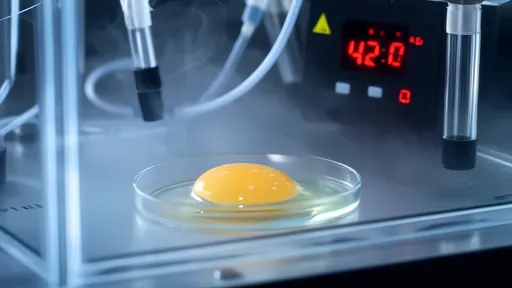

The concept emerged from observing how hot spring waters maintain remarkably consistent temperatures year-round, typically hovering between 37-42°C – strikingly close to human body temperature. Traditional onsen tamago (hot spring eggs) are typically cooked at higher temperatures for shorter durations, resulting in a custard-like texture. The new approach instead mimics the slow, steady warmth of avian incubation, but with a culinary rather than reproductive purpose.

Dr. Haruto Yamamoto, the thermal biologist leading the project, explains: "We're not trying to hatch chicks – that would require specific humidity and rotation conditions. What fascinates us is how prolonged exposure to this narrow thermal band affects the egg's proteins, fats, and carbohydrates differently than conventional cooking. The results challenge our definitions of what constitutes 'cooked' food."

The process begins with fresh eggs carefully sealed in food-grade silicone pouches, then submerged in thermal pools maintaining a precise 38.5°C. Unlike brief hot spring egg preparations that might take 30-45 minutes, these eggs remain immersed for extraordinary durations – anywhere from 12 hours to three days. Temperature stability proves crucial; even half-degree fluctuations can dramatically alter outcomes.

What emerges from these prolonged warm baths defies conventional egg textures. The 18-hour eggs develop a peculiar duality – yolks achieving a spreadable consistency resembling cultured butter, while whites remain translucent with the viscosity of a light syrup. At the 36-hour mark, biochemical changes become more pronounced. Natural enzymes in the egg begin breaking down proteins into amino acids, creating unexpected umami flavors without any microbial fermentation.

Food safety concerns naturally arise with such unconventional preparation. The team implemented rigorous testing protocols, monitoring for bacterial growth and regularly checking pH levels. Surprisingly, the slow warming process appears to activate the egg's natural antimicrobial properties more effectively than sudden heating. Lysozyme, an enzyme present in egg whites, shows particularly robust activity at these sustained temperatures.

Culinary professionals who've sampled the results describe a revelation in egg texture and flavor. Chef Emiko Sato of Kyoto's renowned Hassun restaurant notes: "The 24-hour eggs possess a custard-like richness without any added cream or sugar. When lightly salted and served over rice, they achieve this incredible melting quality that conventional soft-boiled eggs can't match."

The experiments have yielded unexpected scientific insights beyond gastronomy. Researchers noticed that certain egg proteins denature in distinct stages at these low temperatures, unlike the rapid, simultaneous changes occurring during boiling. This has sparked interest among biochemists studying protein behavior, with potential implications for pharmaceutical development.

As word of the project spreads, hot spring resorts across Japan are beginning to offer "extended stay" egg incubation as a guest experience. Visitors can lower their personally selected eggs into designated thermal pools, returning hours later to enjoy the unique results. This participatory aspect has proven particularly popular, blending culinary curiosity with the meditative qualities of hot spring culture.

Looking ahead, the research team plans to explore variations using different mineral compositions in the thermal waters. Early indications suggest that sulfur-rich springs may influence the egg's flavor profile, while alkaline waters could affect protein unfolding patterns. There's also growing interest in applying similar low-temperature techniques to other delicate proteins like fish or plant-based alternatives.

This unusual intersection of geothermal energy, food science, and patience challenges our most basic assumptions about cooking. As Dr. Yamamoto reflects: "We've spent centuries developing ways to apply intense heat quickly. Perhaps there's equal value in learning what happens when we apply gentle heat slowly – letting time and temperature work together in unexpected ways." The humble egg, it seems, still has secrets to reveal when we're willing to wait for them.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025