The art of fermentation has long served as a culinary bridge between cultures, transforming humble vegetables into vibrant, probiotic-rich staples. Nowhere is this more evident than in the parallel traditions of Korean kimchi and German sauerkraut. Though separated by thousands of miles, these two fermented cabbage dishes share surprising microbial connections while maintaining distinct personalities shaped by their terroir and traditions.

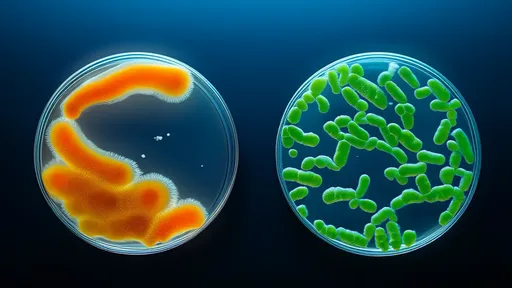

At first glance, kimchi and sauerkraut appear worlds apart. The Korean classic bursts with fiery red chili flakes, pungent garlic, and funky seafood undertones, while its German counterpart presents a pale, sour simplicity. Yet beneath these surface differences lies a fascinating microbial conversation. Both rely on lactic acid bacteria (LAB) to work their magic, but the specific bacterial cast varies dramatically between the two.

The fermentation journey begins differently for each. Traditional sauerkraut relies on spontaneous fermentation, where naturally occurring LAB on cabbage leaves initiate the process. This results in a predictable succession of bacterial species: Leuconostoc mesenteroides starts the party, followed by Lactobacillus brevis, with Lactobacillus plantarum finishing the job. The German method's simplicity - just cabbage and salt - creates this consistent microbial pattern across batches.

Kimchi's microbial landscape proves far more complex. The Korean staple's elaborate seasoning paste introduces a diverse array of microbes from ingredients like garlic, ginger, and chili powder. This creates what scientists call a "inoculated fermentation," where multiple LAB strains compete from the outset. Studies reveal dynamic shifts in microbial populations throughout kimchi's fermentation, with Weissella koreensis, Leuconostoc citreum, and various Lactobacillus species taking turns dominating the ecosystem.

Climate plays a crucial role in shaping these microbial communities. Sauerkraut typically ferments in cooler European temperatures around 18°C (64°F), favoring slower-growing LAB strains. Kimchi often ferments at warmer Korean room temperatures around 24°C (75°F), accelerating microbial activity and creating more rapid flavor development. This temperature difference helps explain why sauerkraut requires weeks to mature while kimchi often reaches optimal flavor within days.

The seasoning differences between the two ferments create distinct microbial habitats. Sauerkraut's high salt concentration (2-3%) selects for salt-tolerant LAB while inhibiting unwanted bacteria. Kimchi's lower salt content (1.5-2.5%) allows more microbial diversity, but the addition of antimicrobial ingredients like garlic and ginger creates alternative protective barriers. These differing preservation strategies result in unique bacterial profiles for each dish.

Modern sequencing technologies have revealed unexpected overlaps between the two traditions. Researchers have identified Lactobacillus sakei in both kimchi and sauerkraut, suggesting some LAB strains transcend cultural boundaries. This microbial crossover hints at potential universal principles in vegetable fermentation, where certain bacteria naturally dominate regardless of geographic origin.

Health implications of these microbial differences remain an active research area. Both kimchi and sauerkraut deliver beneficial probiotics, but their distinct bacterial compositions may interact differently with human gut microbiomes. Preliminary studies suggest kimchi's greater microbial diversity could offer broader health benefits, while sauerkraut's predictable LAB strains might provide more consistent probiotic effects.

The fermentation duration further distinguishes these culinary cousins. Sauerkraut's longer fermentation typically results in higher lactic acid concentration and lower pH, creating its characteristic sharpness. Kimchi's shorter fermentation preserves more varied organic acids, contributing to its complex flavor profile that balances sour, sweet, and umami notes.

Interestingly, both traditions have developed methods to maintain microbial continuity across batches. German sauerkraut makers sometimes use "starter liquid" from previous batches, while kimchi makers traditionally bury their jars in the same earth to maintain consistent fermentation temperatures. These practices, developed centuries before microbiology existed, demonstrate intuitive understanding of microbial ecosystems.

Climate change presents new challenges for both traditions. Rising temperatures may accelerate kimchi's already rapid fermentation to undesirable levels, while warmer winters could disrupt sauerkraut's slow cold fermentation. Some producers are turning to controlled fermentation environments, potentially altering the microbial profiles that give these foods their traditional character.

Consumer preferences continue to evolve both products. Modern kimchi varieties show reduced salt content to meet health concerns, which may impact its microbial stability. Contemporary sauerkraut makers experiment with flavor additions that introduce new bacteria, blurring the lines between these two fermentation traditions.

Scientific interest in these fermented foods extends beyond culinary applications. Researchers study kimchi and sauerkraut microbiomes for insights into microbial ecology, food preservation, and even space food development. The International Space Station has conducted experiments with kimchi fermentation in microgravity, while European scientists explore sauerkraut's potential in sustainable food systems.

As globalization increases, the microbial exchange between these traditions grows. Some Korean-German fusion restaurants now serve "kimchikraut" hybrids, creating entirely new microbial ecosystems. These innovations raise questions about food authenticity while demonstrating fermentation's endless capacity for reinvention.

Ultimately, kimchi and sauerkraut stand as testaments to humanity's shared fermentation heritage. Their microbial differences reflect cultural diversity, while their underlying similarities reveal universal truths about our relationship with the microbial world. As science continues decoding these complex ecosystems, we gain deeper appreciation for how these humble fermented vegetables connect us across continents and centuries.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025